Apostles of Art - William Morris

In this series, continued from last month's successful interview, when a portrait of William Morris was published, it is intended to set before students of art some account from authoritative sources of the great modern teachers, their life and doctrine. This first article is republished from a lecture delivered by Mr. F. S. Ellis before the Applied Art Section of the Society of Arts, in whose journal it subsequently appeared.

I think it may fairly be said that the life-work of William Morris, as given to the world, began in his student days with the founding of the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine. From the way he mentions this publication, I infer that Mr. Vallance was unaware that Morris bore the sole cost of its production. Under such circumstances it is remarkable that it should have lasted through a year. I should think its doing so was due only to Morris’s hatred of anything incomplete. The twelve months rounded it off, so to speak. Mr. Vallance mentions, as though it were a fact, that Morris kept a copy of this book under lock and key by reason of the great store he set upon it. This statement must be due to some misunderstanding, for he certainly set no store whatever by the volume, and kept nothing under lock and key; even his watch-key was usually astray.

William Morris as a Writer

The same writer discusses the question of reprinting such articles as Morris wrote for the magazine. Of that I can only say that I should regard it as a ghoulish proceeding, and a dishonour to the author’s memory, who again and again forbade their reproduction. I am happy in thinking that there are yet some years before anyone dare reprint these articles without permission, and that before that time arrives I shall, in all likelihood, be beyond the knowledge of such matters.

[Re-Editor's Notes] Interestingly, we have found copies of his magazine works. I are re-publishing selected articles from The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine. I consider this magazine a must-read for anyone interested in William Morris as a publisher.

Having emancipated himself from the prospect of a clerical career, what could be more natural than that he should look to the practice of architecture as a profession, and with that idea article himself to the man who was in those days looked upon as an oracle in that branch of art? But a year’s experience in Mr. Street’s office, and the clearer perception of what architecture should be, more especially that Gothic architecture to the love of which his soul was wedded, caused him to see the impossibility, under present conditions, of attaining to and carrying out his ideas, and he therefore sacrificed the remaining term of his articles and turned his attention to other matters.

That William Morris might with success have followed the profession of a painter is demonstrated by the excellent portrait of his wife, painted before his marriage in 1859, which has come to light during the past year, after being for a long period supposed to be lost altogether. But I believe he felt that as a painter he would be overshadowed by the surpassing genius of his most intimate friend; his own saying was that he could not make his figures move. That he did not persevere in his studies in that direction was assuredly a great gain to the world at large, for, whatever distinction he might have gained as a painter and a poet, it is obviously impossible that he could in that case have achieved the great work as a handicraftsman and designer for which all those who have any eyes for beauty are so largely in his debt.

William Morris as a Poet

The year 1858 is marked as an important one in his life by the publication of his first volume of poems. It is no wonder, seeing how entirely original was the note struck by William Morris, that the book was not very heartily received by the public. It would have been a marvel had it been otherwise. It was offered to several publishers, and among others to Mr. J. W. Parker, proprietor of Fraser's Magazine a person considerably esteemed in those days, as I well remember, for a man of taste and a fine critic. He declined to publish the volume, and after it appeared had, as appears from a letter which has lately come to light, no better idea of the value of the verse than that "nineteen-twentieths of it was the most obscure, watery, mystical, affected stuff possible."

The genuine and earnest Mediævalism of the author was altogether lost on Mr. Parker. That the volume was not an immediate success is not, as I have said, to be wondered at, for no book that is out of harmony with the spirit of the age can be expected to succeed until interest in the movement of it is awakened. Two young men, who in their maturity are still among us (Dr. Garnett, who has honoured me by his presence in the chair today, and Mr. Joseph Knight), raised their voices, through the press, in appreciation of the new singer; but that the volume had not a very rapid sale was evidenced by the fact that some seven years later I bought from Messrs. Bell and Daldy the copies that then remained unsold, amounting if I remember rightly, to some thirty or forty. But that the "Defence of Guenever" met with no greater appreciation on its first appearance is—I think easily accounted for— unless the reader has some knowledge of the "Romance of King Arthur" and "Chronicles of Froissart," and, indeed, of the Mediæval spirit generally, it must be mere affectation to pretend to understand and enjoy the poems in Morris’s first publication; as well might an Oriental who had never heard of London affect to enjoy the humours of "Pickwick."

A good deal has been said about printing other poems written about the same date, which the author preferred to leave unpublished. I am happy in knowing that the one person whose authority would be needed for the publication of them has decided against it, and will, I trust, make such provision as shall prevent them being put into print at any future period. He was too capable a critic of his own work for there to be any justification for publishing that which he desired to consign to oblivion.

William Morris as an Architect

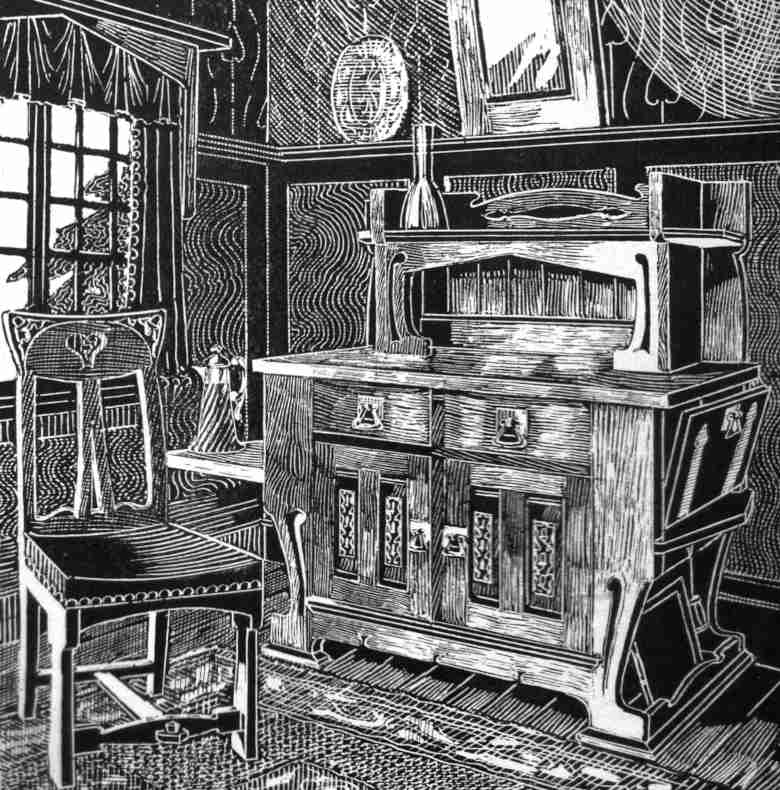

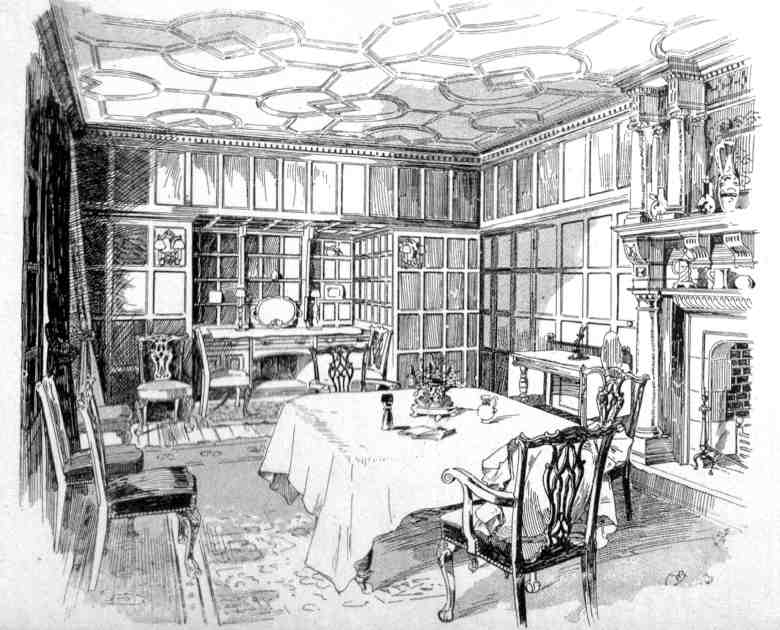

Architecture and painting abandoned as the occupations of his life, William Morris's practical mind addressed itself to the task of showing that it was possible, while perforce shutting one's eyes to the exterior hideousness of ordinary houses, to do something towards making the interiors more tasteful and beautiful than they had been for many a long year—reversing, in fact, the old saying concerning the cup and the platter.

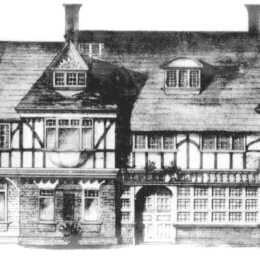

The house designed for William Morris by his lifelong friend, Mr. Philip Webb, was, perhaps, if we except some attempts in the pseudo-Gothic style, the first in the England of the nineteenth century to be arranged and decorated in a departure from the hideousness of deal doors painted and grained to look like oak or maple, staircases covered with mustard-coloured paper and squared in blocks to imitate some sort of marble that never existed, hangings usually of a dull heavy rep, and, in the wealthier houses, stuffs equally ugly, if more costly, varied in summer by preposterous sham lace, black horsehair chairs, ponderous yellow mahogany sideboards and flock wallpaper. Those who are old enough to remember what it was all like will, I think, bear me out when I say that, though our dwellings of today may not all of them be models of good taste, they are certainly better than they were in what we may call the age of antimacassars and Berlin wool work.

It was at this time that William Morris set himself to understand the method of ancient needlework and embroidery. To make himself completely master of how it was done he obtained some pieces of ancient work, carefully took them to pieces thread by thread, and thus made himself completely acquainted with the mode of construction, and then fell to designing patterns and figures, and worked the first piece with his own hands. The result was a series of noble needlework figures for panels in the Upton house. I well remember with what surprise and delight it was that I first beheld these pieces of handicraft at Queen Square, and what a revelation of the possibilities of modern needlework it was to me. It seemed to carry one back to another world. The series as originally designed was never completed; four of the panels are now, I believe, in the possession of the Earl of Carlisle, and four or five others are preserved elsewhere.

William Morris as an Interior Designer

It speaks volumes for the vigour and hopefulness of the man that he ventured to set forth, so to speak, singlehanded, on the task of awakening people to a sense of the hideousness that surrounded them and the possibility of something more artistic and beautiful; for although he associated himself with other men of genius and ability, from whom he received most valuable aid and support, it was, in truth, the remnant of his fortune that furnished the means of beginning the work which he and his friends undertook.

How he threw himself earnestly into the project is witnessed by the fact that he left his pleasant house at Upton and came to live in the smoke of central London that he might give himself wholly to it. It is needless for me to go into the history of the establishment of the firm of Morris, Marshall. Faulkner & Co., which in outline is an oft-told tale, and will doubtless be given at full in the biography.

As he has told us himself in his lecture entitled Making the Best of It, delivered before the Trades Guild of Learning at Birmingham in 1880, it is useless to suppose that any quick and sudden change could be made for the bettering of the outward forms of the houses which most of us, by no choice of our own, are compelled to inhabit. The only thing to do, therefore, was to provide the means of making the interior surroundings more or less beautiful by wholesome and pleasing decoration of the walls to begin with, and then by designing tasteful stuffs for curtains and hangings, and furniture less cumbersome and unsightly, both in form and material, than was commonly procurable at that period.

Both wallpapers and textile fabrics were at first very simple, but not the less admirable therefore, but of later years they grew in many instances to be more rich and costly according to the demand that arose for them. How thoroughly William Morris understood his aims and his work is manifest in every line of his invaluable lectures entitled Hopes and Fears for Art delivered at Birmingham, London, and Nottingham, between 1878 and 1881.

What can be more to the purpose than these words on wall decoration?

"Every line must have a distinct idea in it, some beautiful piece of Nature must have pressed itself on our notice so forcibly that we are quite full of it, and can, by submitting ourselves to the rules of art, express our pleasure to others and give them some of the keen delight that we ourselves have felt. If we cannot do this in some measure our paper design will not be worth much, it will be but a makeshift expedient for covering a wall with something or other, and, if we really care about art we shall not put up with something or other, but shall choose honest whitewash instead, on which sun and shadow play so pleasantly, if only our room be well planned and well shaped, and look kindly on us"

How completely do these words reveal to us the real secret of William Morris’s success as a designer, namely, the perfect grasp that he had of his subject and the spirit of love and enjoyment with which he bent to his work, so that it was a real pleasure to him, destitute of toil and pain.

William Morris’s designs for wallpapers amounted to fifty entirely distinct patterns, which are worked in no less than 237 different colourings, every one of them arranged and directed by himself with that marvellous and unerring instinct for harmony of colour which was one of his most wonderful gifts and one of his most remarkable characteristics. So great is the difference made by the interchange of colours that the same pattern, to any but an expert and practised eye, would appear to be altogether distinct. This is no mere opinion of my own, but a fact that is proved by everyday experience. Then he produced forty-two designs in printed cottons in 159 variations of colour, thirty-nine designs for woven materials set out in 164 colourings, and a very large number of elaborate patterns for carpets and rugs of different textures, sizes and varying methods of manufacture.

In the Birmingham lecture, from which I have already quoted, the author is at the pains to give most valuable hints for the arrangement and decoration of a house, which are well worth the study of all who desire to make the interior decent, whatever the exterior may be, for which, in truth, usually the occupant is not accountable. One part of the exterior he does make useful suggestions for, namely, the setting out of the garden, wherein assuredly as much taste may be shown as in the decoration of the house, and it is, moreover, much more easy of execution and less costly, for once set going in the right way it will in a great measure care for itself, and richly repay the attention bestowed upon it.

I do not hesitate to say that, but for the lifework of William Morris, the amelioration of commonplace ugliness, which may be traced in thousands of houses, would never have come about, but things must inevitably have gone from bad to worse. No doubt a large part of the world persists and will persist in preferring ugliness to beauty—so much the worse for it.

Sir W. B. Richmond, in his eloquent address to the students of the Royal Academy, has well said, "The fine arts are a necessity to a small public; the handicraftsman is a necessity to all; both are desirable, one is essential."

I think one might gloss this saying by the remark that the handicraftsman of taste and judgment ought to be especially considered necessary to the possessor of works of pictorial fine art, for what, I would ask you, is more discordant or distressing to the eye—I might say, indeed, what is more ludicrous—than to behold grand pictures hung in a room or gallery hideous in colour, amid ostentatious but tasteless surroundings?

At an early period of his artistic career William Morris gave much attention to the manufacture of stained-glass. No one who takes an interest in the subject can doubt that he exercised a very beneficial influence over it in respect of tone and colour, for which he had such an unerring eye. He had, moreover, the extraordinary advantage over all other practitioners in the art of being able to command the willing and friendly services, in design, of Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown, and specially of Burne-Jones.

This alone would suffice to give the work William Morris carried out a most important and notable distinction. Yet I believe that he regarded his work in this supremely difficult art with less satisfaction than any other to which he devoted himself. He has, in his masterly and most admirable article on the subject in Chamber's Encyclopædia, shown us how fully and thoroughly he knew what he was about. Of later years he recognised how great a mistake it was to put new glass into ancient Gothic traceries, savouring in truth of the worst form of "restoration," and steadily refused to join in such work.

It may not be, as he has asserted strenuously in the article mentioned above, a "lost" art, but it is assuredly a dead art—as dead as the men who carried it to perfection in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Its spirit was the spirit of the Middle Ages, and that cannot live in the nineteenth century, though we may drag forth the lifeless shadow of it. He was painfully aware of the monstrous incongruity of the modern practice of putting a dozen or more styles of glass into one building.

Glimpses of Good Houses

The absurdity is hardly less, and the irritation to the spectator would be scarcely greater if a dozen different architects were commissioned to design the body of a church, employing styles varying from the Byzantine of the seventh century to the Renaissance of Inigo Jones in its various parts and divisions. The whole being mere imitative work—a Norman choir, a Byzantine nave, south transept Early English, north transept Renaissance, and so on. Yet that is what is commonly done with stainedglass.

What think you would have been the effect of the Kelmscott Press Chaucer had it been illustrated by a dozen different artists in as many different styles? If anyone desires to test for himself the truth of what I have advanced, I recommend an inspection of Wells Cathedral by way of example. The glorious east window, full of indescribable beauty, remains as a witness against the monstrous crudities and platitudes that surround it on every side to the utter degradation of a noble branch of ancient art.

I hope it will not be supposed, when I protest against the absurdity of putting different styles of architecture or glass into one building, that I am ignorant or unappreciative of the value and interest of historical accretion in a building, which is a vastly different thing from feeb imitative confusion and contradiction.

Our November article on William Morris discusses his intersection of wallpaper and publishing poetry. What is it that brought Morris to drive industrials craftsmanship to the United Kingdom? It is Morris' business success that stands memorably tall.