Needlework Notebook, by Miss Clive Bayley

One of the finest pieces of tapestry recently brought into England is to be seen at 11a Church Street, Kensington. It is a magnificent hanging of a room, and might have been made yesterday, so perfectly is it in repair. A portion of it has been cleaned, and in its original state it can hardly have been fuller or richer in colouring than now. The high lights are woven in silk, which stands out in brilliant contrast to the deep blues and greens of the rich foliage and landscape.

The size, age, and perfection of the piece mentioned naturally runs up its price into some thousands, and it is not dear at the figure.

While hunting for old pieces of tapestry in ancient chairs or screens one comes across lovely things. In the Chelsea Furniture Company, just out of Sloane Square, there are some very fascinating objets d'arts, both ancient things and replicas of old designs. Old Staffordshire sponge and brush work has a fascination for some folk, with its broad lines and brilliant colours, and here it is to be found in perfection.

Ancient wooden figures from Venice, rich in colouring and with ringed beads, adapt themselves to electric lighting. A chest of burr poplar, the grain of which is so often imitated in old work, has a great charm, and recalls the old raying about the gnarls which is remembered, at least, about the birch knots—called in east Europe Masur wood. If a tree comes between you and a curse, the curse goes into the tree and grows into a knot, and you are saved.

These excrescences, say of Jarrah wood, of "bird’s-eye" maple, of birch and poplar, may thus have a virtue beside that of beauty. A knowledge, however small, of the manner in which any work is done, and of its materials, gives much interest to the collector, and much insight even to the casual wanderer in those streets whose windows are full of choice specimens of their art.

Re-Editor's Note: Wood knots have a history in witch's chests. Our October issue talks about a witch's oak chest that was claimed to be owned by Elizabeth Swann.

Thus, to the embroideress, the varied stitches, the material used, are all full of details which make the very life of her craft. This material was unique at such and such a period, this special thread came from a locality famous for the beauty of its fibre, etc.

Thus, too, in tapestries and general weaving, one is brought into touch with such absolute facts, that it becomes a matter of no uncertainty how or when certain specimens of work were done.

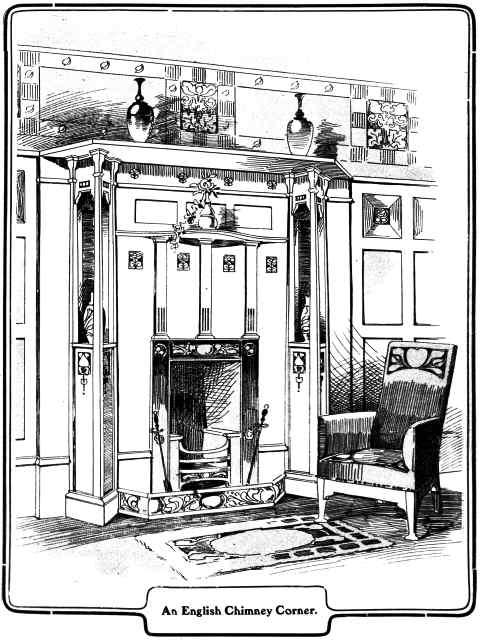

No wonder that enterprising ladies, following their own instinctive love of the beautiful and the taste borne of artistic environment, are seldom contented with collecting household gods for other people, but add to their curiosity shops the natural ambition of placing their treasures in good surroundings suitable to their style and value.

Thus, house decorating and furnishing is an almost inevitable outcome of a store where a Brittany armoire, Jacobean chests, Dutch bureaus and specimens of old china, and old oak furniture seem to demand, nay, clamour for space and congenial companionship as they do in this charming little corner of Chelsea.

Not only are Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Russia reviving these lost industries, but Italy is humbly copying the example thus set, and a very zealous revival of embroidery and (are is being -carried on in the Æmelia d'Ars Institute at Bologna by an Italian Countess. Her chief desire is to have the old drawn linen work resuscitated. She has had hand-made linen from England, but hopes to get it spun and woven in her own country, and so have the whole industry complete as in ancient times.

Re-Editor's note: The United Kingdom is also looking to rebuild its industry. The Macclesfield School for embroidery may well be the pathway. Students leaving the embroidery school will have the skills to create their own arts and crafts masterpieces. I have to wonder if any student went on to sell an important piece on the secondary market. Watch out Bargain Hunt!

A. M. Clive Bayley